Say more context, information needed to determine if firing would be justified

The attorney representing suspended Cannabis Control Commission chair Shannon O’Brien has dismissed as “laughable” the allegations of racial insensitivity leveled against her, but three academic experts on such matters say the issues being raised–especially O’Brien’s use of the word “yellow” to describe Asian-Americans–are worthy of greater exploration.

After reading excerpts from O’Brien’s court filing about the allegations against her, the experts all agreed that more context and information are necessary to determine if O’Brien should be fired for racial insensitivity. However, in telephone interviews, they raised questions about how O’Brien’s comments might create an uncomfortable workplace for people of color.

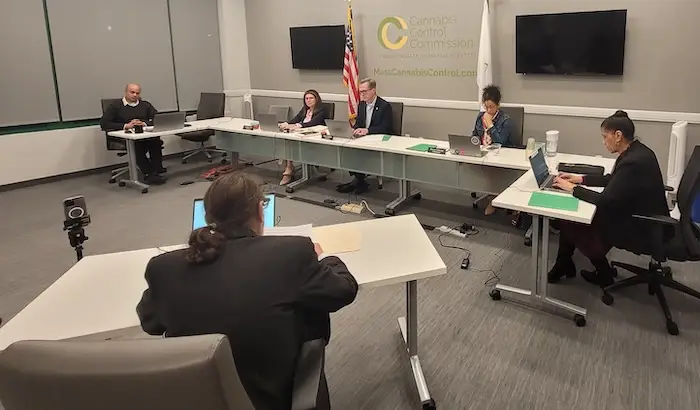

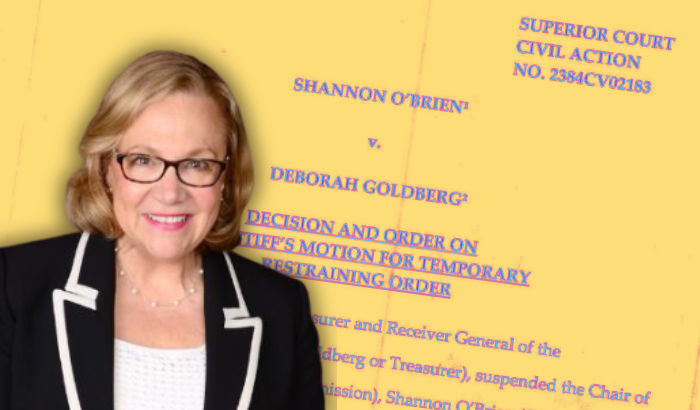

State Treasurer Deborah Goldberg suspended O’Brien with pay on September 14 after an investigation launched by the Cannabis Control Commission accused her of making “racially, ethnically, and culturally insensitive statements.” A second investigation of her dealings with the former executive director of the commission has not been completed yet.

Goldberg and O’Brien have been wrangling in court about the process Goldberg will use in determining whether to retain or fire the commission chair. Goldberg so far has prevailed, winning a judge’s backing for closed-door hearings that the treasurer, who appointed O’Brien to her post, will oversee.

The actual charges against O’Brien have not been publicly detailed by Goldberg, but O’Brien released a letter from Goldberg that details at least four charges of racial insensitivity that were levied against her. O’Brien hasn’t disputed making the comments, but has suggested they are being taken out of context or being overstated to discredit her and remove her from her position.

The comment that has attracted the most attention was O’Brien referring to Asian-Americans as “yellow” in a fall 2022 meeting. In a court filing, O’Brien defended her use of the word by saying that she was repeating the words of “a well-known and respected African-American real estate developer, in which he was explaining how he organized a group of black, brown and yellow investors to create business opportunities for persons.”

According to Goldberg’s letter, when O’Brien was informed that “yellow” wasn’t an acceptable word to use, she said: “I guess you’re not allowed to say ‘yellow’ anymore.” Later, to an investigator looking into her conduct, O’Brien said: “I should have cleaned it up. It’s difficult sometimes to know how to say the right thing.”

Ellen Wu, an associate professor at Indiana University, said “yellow” is not an acceptable word for referring to people of Asian descent. “People today don’t really wish to call themselves that, because ‘yellow’ has a long history [and] long genealogy of being used by westerners, by white American, and Europeans to refer to a very large chunk of the world,” she said. “It’s a reminder of a past in American society and culture when mainstream white Americans very openly despised people from Asia.”

The long history of the word “yellow” is tied in with the xenophobic concept of “yellow peril” which emerged in the mid-nineteenth century. It relied on racist imagery to homogenize Asian-Americans from many different Asian countries and paint them as being an existential threat to American society.

Natasha Warikoo, a professor of sociology at Tufts University and an expert on racial and ethnic inequality in education, emphasized that the problem with using the word “yellow” is that Asian Americans don’t self-identify with that word.

“All of these racialized terms are strange, but [yellow] is one that, unlike the term “Black,” which was eventually adopted by African-Americans, has never been a term that Asian Americans self-define as, and so to call us using that term is problematic,” said Warikoo. “And it’s kind of shocking that a public official wouldn’t know that or claim to not know that.”

Warikoo further critiqued the way in which O’Brien defended herself for using the word “yellow.”

“I don’t have a huge problem with someone slipping up and using a term that they don’t realize is offensive to some people and then apologizing for it,” said Warikoo. “I do have a problem with them responding by saying that another person of color used that term. I don’t think that’s taking responsibility for the harm that you perhaps unintentionally created. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the person [she claims said the word] is Black. So I think that’s problematic.”

Kevin Woodson, a law professor at the University of Richmond and the author of The Black Ceiling: How Race Still Matters in the Elite Workplace, said O’Brien’s claim that she was merely quoting someone else could be exculpatory but that her words could still make people uncomfortable in the workplace.

“I do think it’s tricky if other people are using that language, and if she used it in a context where it would’ve been clear that there was no malicious intent, then I can understand why she was confused,” he said. “But that doesn’t change the fact that it can make people who work with her and work under her deeply uncomfortable.”

The three other complaints that O’Brien shared with the court were made by one of her fellow commissioners, Nurys Camargo, who is of Dominican-Colombian descent and holds the social justice seat on the commission. O’Brien made these allegations public because she says that these were the only allegations attributable to a specific person. The rest, according to O’Brien, were made by anonymous staff members recruited by Camargo in a plot to get O’Brien fired.

One of Camargo’s allegations was that O’Brien assumed that Camargo would know Sen. Lydia Edwards of East Boston because they are both women of color working in Massachusetts government.

Woodson speculated that, even if that was a fair assumption to make, O’Brien seems to speak in a certain “unfiltered” and “blunt” way that can “offend or embarrass people.”

“To be honest, the way that networks of women of color in certain relatively small elite circles work, a lot of us would assume that there’s a good chance that they know each other,” said Woodson. “But to say it that way takes that assumption and vocalizes it in a way that can make other people feel uncomfortable. And that’s something you can’t do if you don’t have the goodwill and rapport with the person…because it’s going to make them just wonder just how much you assume on the basis of race.”

Camargo also accused O’Brien of making “public statements that could reasonably be perceived as creating the impression” that minority candidates were not as well qualified as her for the chairman’s job. O’Brien has argued that it was actually Goldberg who made the comments about not wanting to put Camargo in the chair position.

O’Brien also said on various occasions that Cedric Sinclair, the chief communications pfficer of the CCC and an African-American man, was Camargo’s “buddy.”

“If she made the [buddy] comment because they were two non-white people, it would suggest that she makes certain assumptions about non-white people either being all in cahoots with each other or somehow having secret alliances,” said Woodson. “But that is a big if. It would depend on if that’s why she actually made that comment or if she had other reasons to believe that they were in fact buddies.”

O’Brien has claimed in court filings that Sinclair and Camargo indeed were “buddies” and that they were “‘comarades in arms’ in their war against Chair O’Brien.”

At the CCC, much of the policy focus has been aimed at making sure that people who have historically been harmed by the “war on drugs,” and excluded from policy spaces for racial reasons, can have equal participation in both the profit participation and the decision-making. Woodson said that the problem with comments like the ones that O’Brien has made is that they can make people of color feel uncomfortable and wonder what other assumptions O’Brien might be making on the basis of race.

“When you’re worried that your senior colleagues might harbor racial biases, one common response is to speak up and speak out a lot less,” said Woodson. “And that can marginalize people in a number of ways. It’s also very stressful having to worry about whether this person has certain negative assumptions about you, about your abilities and whether you’re competent, whether you’re intelligent.”

Warikoo offered advice to O’Brien going forward.

“I would hope that O’Brien reflects on these experiences rather than getting defensive and [that she] tries to repair and recognize and do better,” said Warikoo. “Rather than her leaving this position and taking another position and continuing to make those same kinds of comments, I would hope that she would be provided the space to grow and learn. It’s hard because people of color are the ones who are expected to move on.”

This article was reprinted with permission from CommonWealth Beacon. You read the original version here.