“The way THC percentage is calculated … should reflect the consumer’s experience. Otherwise it’s hard to say what the purpose of putting the number on the label is.”

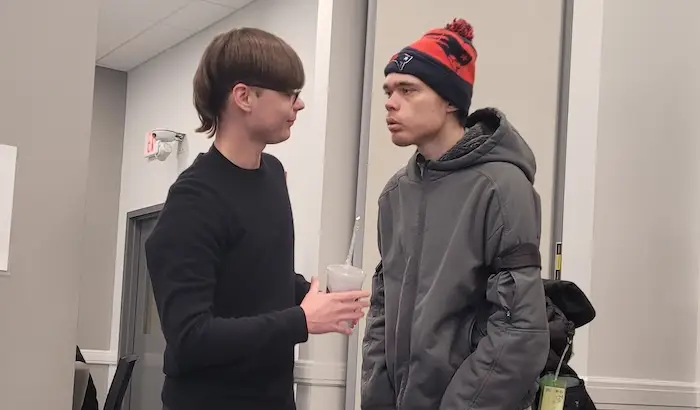

It kind of sounded like a tag-team wrestling match.

In one corner was Chris Hudalla of ProVerde Labs along with Jeff Rawson from the Institute of Cannabis Science.

In the other, Massachusetts regulators.

Members of the Cannabis Control Commission weren’t actually present for the bout, but they got body-slammed nonetheless. The referee, podcast host Mike Crawford of the Young Jurks (who has contributed to Talking Joints Memo in the past), also joined the pile-on.

Many Young Jurks episodes go deep on cannabis-related topics that most outlets barely graze, and we especially recommend those in which they dive into the death of Trulieve employee Lorna McMurrey plus the follow-ups on that company’s exit from the Massachusetts market. Another standout, this week’s interview with Hudalla and Rawson really packs in everything—hooks (a play-by-play on potency inflation), crosses (Crawford has a scoop about a potential ignored conflict-of-interest involving Trulieve and testing), and haymakers (asked if the CCC is managing the testing concerns brought up on the episode, Hudalla says, “There seems to be no interest in addressing this”).

For all the dirty technical and scientific details, we recommend giving the episode a full listen. But with the CCC’s Cannabis Advisory Board’s Research Subcommittee meeting this Friday, and as state lawmakers consider bills addressing testing on Beacon Hill, we excerpted some of the most interesting jabs and knockout punches from the interview with Hudalla and Rawson below …

On the prevalence of potency inflation …

Hudalla: We call it “potency pumping” and it relates to chicken pumping. The USDA permits injection of up to 15% water weight into chicken, and so every year consumers pay $2 billion just for water weight that’s been added to their meats. That is acceptable under USDA [regulations], and only in the past 10 years is it required to be put on the label.

We started looking at what’s been happening with potency inflation, 20 to 30% inflation of what’s on the label compared to what’s in the package, and if we take that same kind of approach to meat pumping and apply it to potency pumping—wholesale and retail prices are strongly tied to the total potency, higher potencies bring higher margins—we estimate that in 2022 alone, Massachusetts consumers paid about $90 million for THC they did not get. … It’s not only a consumer safety issue, but it’s also a consumer fraud issue.

On market manipulation …

Hudalla: There are a number of ways in which this can be achieved. One of the ways is by drying or correcting potency values based on a theoretical 0% moisture content, [even though] nobody is selling their flower at 0% moisture. Typically in retail I would expect maybe 8 to 12% moisture in the flour, but when the potency for that particular sample is measured, and that excess moisture is factored out, if you have a 10% moisture in the flower, it’s going to inflate the potency by that same amount by factoring out that water weight.

On the underlying issue …

Hudalla: Every single lab that’s measuring potency in Massachusetts is using a different calculation. We might all measure in the same way, but how we take those numbers and massage them and manipulate them for reporting is different lab by lab. Some labs add in isomers.

Rawson: It’s obvious to almost anyone that the way THC percentage is calculated … should reflect the consumer’s experience. Otherwise it’s hard to say what the purpose of putting the number on the label is.

On the need for additional regulatory guidance …

Hudalla: Are synthetic cannabinoids permissible in the Massachusetts market? Do we add Delta 10 into the total THC calculation? In the total THC calculation do we do the mathematical decarboxylation that is required under federal [policy] and [by] every other state agency when we report total THC? Do we moisture correct? These are all questions we’ve been begging for guidance on for years, and in our most recent guidance from the CCC, they basically said it doesn’t matter, you can do anything you want—how and what you report is a business decision, it’s not a regulatory decision. For a regulator who’s responsible for the Massachusetts cannabis program, for them to consider potency reporting a business decision is alarming.

On attempts to fix the problem …

Rawson: I provide honest data about weed and I do that by testing products off the shelf and by analyzing and aggregating testing. By doing that you can figure out some of the things that labs might do and which labs have trouble failing samples for mold ever. …

Last July I submitted my first FOIA request for a data file from the seed-to-sale system. … The CCC eventually did make an effort to provide them, but the data set they provided was pretty badly flawed. … That points to the fact that some of their data team may have some passing familiarity with the database, but they’re not capable of the systematic kind of analysis that you would need to do in order to actually make use of it.

On legal remedies …

Hudalla: In other states, we see class action suits becoming a part of the business. Everybody wants to make really good margins but sooner or later the consumers are going to rebel and unfortunately it will probably be lawsuits that [will bring about change]. Certainly the regulators aren’t going to be doing anything about this. They’ve been aware of it, we have been talking to them for three years on some of these topics. They just say they’re working on it, they’re working on it. It’s kind of a skipping record.

On the damage already done …

Hudalla: One of the sad results of this is that we have a huge amount of data collected in the state’s database for total potency and that collection of data is essentially garbage because it’s tainted. When you look at a total TAC value in [the state’s seed-to-sale system] Metrc, you don’t know how that data was come to in terms of the manipulation, so if I look at two total THC values in Metrc, one could be accurate and the other could be 20 or 30% higher than what it really is because of the way the data was handled.