How a one-time conduit to power got snared in an FBI wiretap

O’Donovan wanted a cut of the store’s profits that could hit $100,000 to $200,000 a year once the pot shop was operational

On February 10, 2021, Mike Buckley nosed his car into a church parking lot in Medford, just over the border the city shares with Somerville. An old friend, Sean O’Donovan, had texted him earlier in the day to set up an in-person rendezvous, and they agreed to meet at the parking lot behind St. Clement Church, on the edge of Tufts University’s sprawling campus.

Buckley’s car sidled up to O’Donovan’s car, and they rolled their windows down. Buckley assumed O’Donovan, an attorney, wanted to wrap up a loose end of a legal case involving another member of Buckley’s family.

But O’Donovan, a longtime player in Somerville politics who had served 13 years on the city’s Board of Aldermen and a stint on the school committee before that, had something else on his mind. O’Donovan had turned to fully focus on lobbying and lawyering after leaving office, and he wanted Buckley’s help with a marijuana business client looking to open a Medford store.

The panel of local city officials tasked with helping choose a marijuana company to receive a host community agreement – crucial to getting an operating license from the state – planned to hold its first meeting the next day. Buckley’s older brother Jack, because of his position as Medford’s police chief, was a member of the panel, and the mayor of Medford, who would ultimately make the call on who to choose for the agreement, valued his opinion.

O’Donovan said he would pay Mike Buckley $25,000 to talk to his brother about his client’s application when it came before the panel. Buckley was noncommittal. For that amount of money, Buckley thought, it had to be more than a conversation.

On his way home that night, the full weight of O’Donovan’s request hit him. He swore and banged on the steering wheel. Buckley wasn’t a lobbyist. He didn’t have any experience or interest in the marijuana industry.

When Mike Buckley called his brother and relayed what O’Donovan said, Jack cursed, too, and hung up on him. Jack Buckley eventually called back. He said the FBI would be in touch. They wanted Mike Buckley to wear a wire.

On February 7, three years after that first parking lot conversion, a federal judge will sentence O’Donovan, who was convicted of attempting to bribe Jack Buckley in connection with the effort to grease the skids for the pot shop applicant.

The judge rejected defense efforts to introduce the idea that O’Donovan had been entrapped, and the jury didn’t buy the argument that his actions amounted to perfectly legal, everyday lobbying. In October, O’Donovan, 56, was found guilty on three counts; he potentially faces decades in prison.

Corruption cases, and attempted prosecutions, were once a dime a dozen in Somerville, long known as a home base for assorted wise guys and sketchy politicians. The city’s reputation was a blessing for the Boston Globe’s Spotlight team, helping the newspaper’s investigative unit win its first Pulitzer Prize in 1972 for stories exposing shady deals. In the 1980s, it was a Somerville state representative, Vinnie Piro, who made headlines for all the wrong reasons. The State House power broker faced federal extortion charges, but was ultimately acquitted in a case where he was accused of taking a bribe from an undercover FBI agent – but then giving the money back three weeks later.

O’Donovan’s trial came and went without much fanfare. The local media scene has shriveled, with the two papers that once served Somerville and Medford having merged in the months before O’Donovan’s arrest and been hollowed out like so many other local outlets. The Boston dailies all but ignored it. Even US District Court Judge William Young, when he was addressing the jury about its duties to ignore coverage of the case, said he hadn’t seen many news reports on the trial, aside from some mentions in “legal blogs.”

This story, with its echoes of another era, is based on reviews of court filings, trial transcripts, public records, and interviews, and includes previously unreported details. Most of the individuals who were asked about the O’Donovan case did not want to speak on the record or did not return a request for comment.

These days, Somerville is known for hipsters and cool cafes, and real estate prices through the roof. Politically, most voters chose Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders over Joe Biden for president. In place of the back-slapping Vinnie Piros who once ran the show, they now send democratic socialists to the State House. Not content to deal only with mundane matters of zoning or municipal finances, the City Council now wades into global conflicts, this month becoming the first community in Massachusetts to adopt a resolution calling for a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war.

In other words, it’s a far cry from the place where Sean O’Donovan grew up and became practiced in the ways of deal-making politics. That makes him a throwback to the days of the city’s old guard, and his story reads like a tale from an earlier time.

FRIENDS IN HIGH PLACES

Before the hipsters and young professionals moved in, before the progressives took over local politics, before the Board of Aldermen became a City Council, and before real estate values soared and the Green Line extended into the city and neighboring Medford, Somerville was most often described as “gritty.”

The Buckleys and O’Donovans, two large Irish families, grew up in that Somerville, in Ball Square, a block apart, and the children attended the same elementary school.

Mike Buckley, after several jobs working city governments, including as a top aide to the mayors of Somerville and Everett, eventually landed a job at Harvard University, where he helped departments put together their budgets.

Sean O’Donovan was the son of a World War II veteran from Ireland’s County Cork who served as a cryptography specialist for the US Army. After a stint as Somerville’s city solicitor in the 1960s, James A. O’Donovan went into practicing law, and the son eventually joined his father’s practice until the elder O’Donovan died in 2016.

Sean O’Donovan was also a protege of Stan Koty, whose family in his 2019 obituary called him “one of the most effective political strategists in Somerville’s history.” Koty served in local elected office and later played key roles in mayoral elections and city government. The same year Koty passed away, Koty’s ex-boss and close friend, Vinnie Piro, the former state rep who beat the attempted extortion charge in the 1980s, also died.

After meeting in elementary school, O’Donovan and Mike Buckley’s paths crossed again inside Somerville’s City Hall, when O’Donovan succeeded Koty as Ward 5’s alderman and Buckley worked for Mayor Joe Curtatone. But by 2021, Curtatone was on his way out, Buckley was ensconced in a new job at Harvard, and O’Donovan’s sway in City Hall had waned. O’Donovan was losing interest in the city’s politics. He was focused on neighboring Medford and its burgeoning marijuana scene.

O’Donovan had locked in a marijuana company as a client years earlier. Brandon Pollock, a New York state native and the CEO of Theory Wellness, first came through O’Donovan’s doors in 2016. Pollock initially looked to Greater Boston to site a medical marijuana store, and a location in Somerville was on the list. When he spoke to a Davis Square landlord about a lease, she pointed him to O’Donovan, who agreed to meet Pollock at O’Donovan’s second office on Tremont Street, steps from Boston City Hall.

O’Donovan bragged about the buildings he helped get through complicated permitting processes, and touted a “very good relationship” with Marty Walsh, the mayor of Boston at the time and future US labor secretary, according to Pollock.

A few months before their sit-down, the Boston Globe had published an extensive story on O’Donovan, with the headline, “Fast track from nobody to City Hall player.” The story detailed how O’Donovan had built influence and easily accessed people inside the building after Walsh’s 2013 election. Chelsea state Rep. Eugene O’Flaherty, who had been O’Donovan’s law partner and shared an office with him on Broadway in Ball Square, had joined the administration as corporation counsel.

Pollock didn’t end up signing the Somerville lease, and after voters legalized marijuana for recreational use through a November 2016 ballot initiative, Pollock’s company changed course and began pursuing licenses for what was expected to be the more lucrative recreational pot market.

When Pollock met with O’Donovan again, it was late 2018, and Pollock was now eyeing Medford. They reached a deal to pay O’Donovan $7,500 a month until the host community agreement was obtained from the city.

But O’Donovan wanted something else far more valuable on top of that: A cut of the store’s profits that could hit $100,000 to $200,000 a year once the pot shop was operational. A clause in the agreement would even entitle his heirs to the profits if O’Donovan were incapacitated or dead. Pollock felt it was too rich a deal. But O’Donovan said another marijuana business was also interested in Medford, and he could either work for Pollock or for them.

As he weighed what to do, Pollock remembered how he’d reached out to Medford’s city attorney, he’d attended City Council meetings, and he’d gotten nowhere. Pollock signed the agreement.

In the years between the agreement and O’Donovan’s rendezvous with Mike Buckley in the church parking lot, there was a change in Medford city government right as the pandemic started. Breanna Lungo-Koehn, first elected to the City Council in 2001 at the age of 21, was sworn in as the city’s new mayor in January 2020. Months later, Medford put in place a cannabis advisory committee, through a city ordinance that called for five members, all city employees, including the chief of police, Jack Buckley. They would rank each applicant, and then send a recommendation to the mayor.

O’Donovan didn’t have a relationship with Lungo-Koehn and didn’t know most members of the panel. But he knew Jack Buckley from their schoolyard days in Somerville. Jack would be his way in. After their parking lot meeting, O’Donovan reached out to Jack’s brother Mike Buckley again and didn’t hear back. He kept pushing for another meet-up, and Mike Buckley, now coached by the FBI and outfitted with a wire, agreed.

In April, a few days before the competing marijuana companies sent in their applications, O’Donovan and Mike Buckley met up again. Mike Buckley said he talked to Jack about O’Donovan’s request. “He didn’t, like, freak out on me, and he didn’t hit me,” Buckley quipped, which seemed to suggest some hope for O’Donovan’s cause.

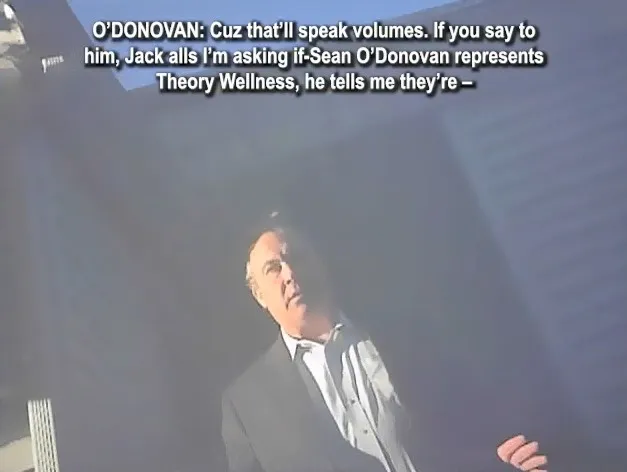

O’Donovan wanted Jack Buckley to give his client a high ranking, and to personally tell the mayor that she should select Theory Wellness. The mayor likes Jack, he continued. She trusts him. “Whoever he gives the nod to, is gonna look great in her eyes,” he told Mike Buckley on video.

THE FIST BUMP

Meetings and communications between the two of them would follow in the months ahead. In late September 2021, they had another confab. Mike Buckley said he had met with Jack over the weekend about the Medford pot shop. Jack did not initially rank your guys in the top three, he said. O’Donovan was surprised. Why?

Back in August, Theory Wellness, which by that point had locations in Chicopee, Bridgewater, and Great Barrington, was hit with wage law violations because they failed to give their 282 employees premium pay on Sundays and holidays, as required by the state, and they needed to pay $300,000 in penalties and restitution. Buckley said his brother was bothered by the violations.

But, Buckley added, because O’Donovan was paying him, Jack would change his ranking in the final vote of the committee. “Beautiful,” O’Donovan said, leaning in to fist bump Buckley in a scene captured on an FBI video recording of their meeting.

“He’s going to move them to the top, No. 1,” Buckley added. “Perfect,” O’Donovan said.

There was another twist, Buckley said. Jack believed his brother was getting screwed, and he wanted proof that Mike would be paid.

O’Donovan appeared annoyed. The company doesn’t want to pay the $25,000 before they win approval, he said. “This is like a mini campaign,” he said, seemingly likening it to an election, with the votes having to come in before a declaration of victory.

O’Donovan wondered aloud during the meeting, and in a later recorded phone call with Mike Buckley, about the various ways he could get the money to Mike, or at least guarantee it. At an earlier meeting, they discussed cash, so “there will be no trace,” O’Donovan said. O’Donovan decided on asking Theory Wellness to commit to the full payment if they prevailed, without going into detail on Buckley’s role.

Days later, as the Medford cannabis advisory panel was wrapping up its deliberations, O’Donovan texted Pollock, the Theory Wellness CEO. “Hi, do I have permission to hire a consultant for $25K? Will need to pay it upon success. I would recommend it.”

Pollock was unaware of the meetings between O’Donovan and Mike Buckley. When O’Donovan’s request came in, Pollock became suspicious and called Jay Youmans, the company’s lobbyist at the state level.

Youmans, who had worked in state government under Deval Patrick and Charlie Baker before becoming a lobbyist, recommended against it, and Pollock in turn told O’Donovan no. “We’re an above-board company,” Pollock said, according to his testimony.

The last meeting between O’Donovan and Buckley took place October 11, 2021. O’Donovan brought $2,000 in cash, with the rest, he told Buckley, “locked and loaded,” as long as Theory Wellness gets the agreement.

If anyone asked about the payment, O’Donovan planned to say Buckley was helping him with Boynton Yards, a development that would bring lab space to an area of Somerville less than a mile from Kendall Square in Cambridge, a hub of life science companies.

On December 2, O’Donovan sent Mike Buckley a text, fishing for the latest news on what was happening with the Theory Wellness application. “Hi. Nothing still, huh?”

Seven months later, in June 2022, FBI agents arrested O’Donovan in West Yarmouth, on Cape Cod, after a federal grand jury returned an indictment charging him with two counts of honest wire services fraud and one count of bribery.

‘NO MEANINGFUL DIFFERENCE’

During the trial, Martin Weinberg, the prominent Boston defense attorney representing O’Donovan, worked to inject reasonable doubt into the government’s case. The judge did not allow Weinberg to use the entrapment defense, and Weinberg is expected to appeal the conviction.

Before O’Donovan’s sentencing, the defense team plans to file a memo, looking for mercy, with letters from more than 40 people who were aided by O’Donovan when he was an alderman and pro bono lawyer.

“That will act as testimonials to all the good he’s done in his life, for clients he’s represented pro bono, family members he’s been a lynchpin to, and for constituents that he used to work tirelessly and selflessly to help,” Weinberg said in an interview. “A man shouldn’t be defined by some unfortunate conversations on tape when he’s done so much for so many over decades.”

During the trial, Weinberg argued that O’Donovan was only requesting that Buckley ask his brother to read the Theory Wellness application, totaling more than 600 pages, one of nine proposals submitted.

There was nothing nefarious about holding that first meeting in a parking lot and not an office, said Weinberg. It took place with the pandemic still raging, and O’Donovan, who regularly spent time with his mother, who was in her 90s, wanted to be careful about his exposure to Covid. And notwithstanding all the evidence presented by the government to the contrary, Weinberg insisted O’Donovan even made clear in the meeting that he wasn’t looking for the police chief to tip the scales. “Tell Jack I want no favors,” Weinberg said, quoting O’Donovan from the FBI recording.

O’Donovan had known Jack Buckley for 50 years, since their schoolyard days. “Why would Sean O’Donovan ever believe that he’s going to trade his reputation, betray his oath, compromise his duties as a police chief?” Weinberg said during the trial.

The government’s case, he continued, rested on Mike Buckley telling O’Donovan that his brother decided to change his vote if he gets paid. It was a lie, “scripted by the FBI,” Weinberg said.

As for the payment, it went to Mike Buckley, a private citizen acting as an FBI informant, not Jack the public official, who was one of five members of a municipal advisory panel, Weinberg argued. The mayor held the ultimate awarding authority. O’Donovan believed that Mike would lobby and advocate for Theory Wellness, Weinberg said.

The other leading contenders for the Medford community agreement had hired an ex-mayor and a lawyer with ties to Medford’s City Hall. “There is no meaningful difference between hiring a family member, as opposed to a friend or former aide or ally, to lobby a public official,” Weinberg added.

Prosecutors said O’Donovan, a “sophisticated attorney” and former alderman, initiated the scheme. If the defense launched into an entrapment argument, prosecutors planned to call another witness. Paul Mochi, Medford’s longtime building commissioner, was also a member of the cannabis advisory panel, and would have testified that in January 2021, just before its first meeting, O’Donovan gave him a 30 percent interest in a real estate deal, even though Mochi had not invested any money and his name had been left off paperwork for the limited liability company taking part in the deal, according to a court filing from prosecutors. Mochi, who quietly retired from city government nearly two years ago, would have also testified that O’Donovan “hounded” him about the Theory Wellness application, and he felt pressured to hand them a high score, prosecutors said.

In her closing argument to the jury, prosecutor Kristina Barclay brought up the celebratory fist bump O’Donovan offered Buckley after Buckley said his brother would change his vote for the money. “It was a bribe. Plain and simple,” she said.

‘INDEPENDENT AND INSULATED’

In the end, Theory Wellness received the highest score from the five-member panel Jack Buckley and Paul Mochi served on. The company secured its host community agreement, received its operating license from the state, and opened its store earlier this month.

If she had taken the stand in O’Donovan’s trial, Lungo-Koehn, the Medford mayor, would have testified that Theory Wellness received the host community agreement from the city on the merits of its proposal, according to prosecutors. “The fact that Mr. O’Donovan believed he could bribe our Chief of Police to influence the mayor to further his own financial standing is completely absurd,” a Lungo-Koehn spokesman told CommonWealth Beacon in an emailed statement, adding that the mayor is “glad that justice was served.”

After he spoke with the FBI in February 2021, Jack Buckley – the real Jack Buckley, not the one portrayed to O’Donovan by Mike Buckley in their wiretapped conversations – walled himself off from O’Donovan’s push for Theory Wellness. Chief Buckley testified in court that he did not know the name of O’Donovan’s client when he scored the applicants as a member of the advisory panel. “I wanted to keep myself independent and insulated from any criminal investigation that was going on,” he testified in court.

The new Theory Wellness outlet, considered its flagship store, occupies a renovated Volkswagen dealership on Mystic Avenue. About a mile away, over the line in Somerville, sits the mixed-use building that O’Donovan owned and used to house his law office, a quick walk from the new Ball Square MBTA Station. Valued at $350,000 in 1999, it sold on January 22 to a realty trust for $1.4 million, according to publicly available records.

Posters from the pandemic, encouraging social distancing and masking up, are still around the building’s entryway. But Sean O’Donovan’s name, once displayed in big white letters on a green background, has been stripped from the sign that faces the street.

This article was reprinted with permission from CommonWealth Beacon. You read the original version here.