Massachusetts State Police purchased surveillance tech that civil liberties watchdogs say invites concerning violations of constitutional protections. Is it too late to put accountability measures in place?

Earlier this year, the Massachusetts State Police announced that it was looking to pay up to $1 million to covertly intercept cell phone information and track locations through a controversial device that civil liberties advocates say can suppress free speech and lead to questionable prosecutions.

Months later, the department purchased one such cell-site simulator from a company that boasts about selling equipment to military and intelligence clients, as well as to police departments nationwide, with the promise of upgrades to the latest location tech. In a jargon-heavy proposal to the MSP, the seller, Jacobs Technology, noted its Engineering Integration Group’s ties to the surveillance state. (You can read the unredacted bid response in full here.)

“Leveraging years of concealment experience obtained from supporting the [intelligence and special operations] communities, EIG is uniquely positioned to apply this skillset to [continental US] law enforcement operations,” the proposal reads. “EIG provides solutions that not only exceed standard [cell-site simulator] specifications, but intuitively provide what Law Enforcement Operators really need to efficiently and effectively protect the public.”

But what the public really needs, according to civil liberties experts, is oversight. Asked about this latest development, they said the Jacobs proposal shows how cell-site simulators can be used to pull in millions of dollars through civil forfeitures and build legal cases while withholding information that leads to arrests. As a result, many are calling for lawmakers to devise regulations to track and explain the use of cell-site simulator tech.

“It’s extraordinarily important [to have a policy]. One million dollars to have a piece of equipment is not chump change,” said Mike Katz-Lacabe of Oakland Privacy, which has tracked these devices in the Bay Area for years and even sued officials to obtain usage information. He continued, “Knowing how it’s used and how many times it’s used is critical for elected officials to make informed decisions about how this sort of thing happens, [as well as] the impacts and ramifications for citizens they represent.”

The state police and Jacobs did not respond to requests for comment. But state Sen. Jamie Eldridge, chair of the Joint Committee on the Judiciary, agreed with civil liberties advocates and said he planned to investigate and take action to create government oversight.

“I don’t think the state police should have gone forward to purchase this simulator,” Eldridge said. “This is another front in the potential invasion of civil liberties. It is really critical for the Mass legislature to better protect people’s privacy, including from law enforcement.”

Fooling phones, praising products

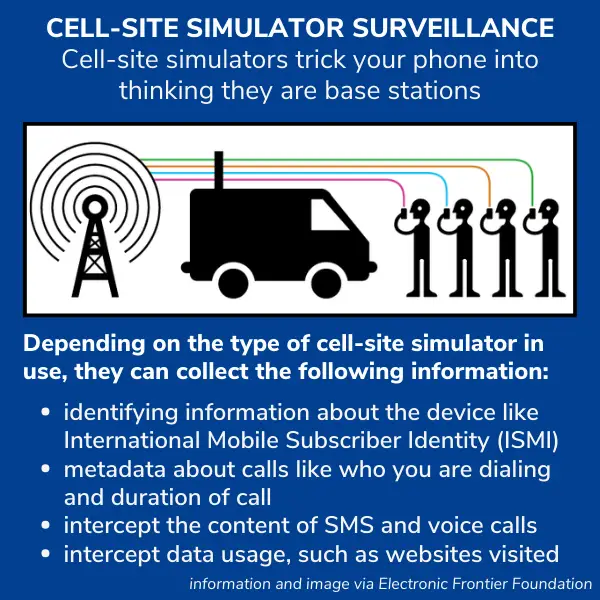

As BINJ reported in February, the state police asked for bidders to provide a cell site simulator—commonly known as a Stingray, after one popular brand name—installed in a Chevrolet Silverado, allowing authorities to potentially collect cell information from thousands of people as they drive through crowded areas. A cell-site simulator works by fooling phones into connecting with it instead of a cell tower; once those phones are connected, police collect International Mobile Subscriber Identifiers from SIM cards. They can then locate individual phones, in the process potentially interrupting actual 911 calls to emergency responders.

Police can also get a suspect’s phone number and then use a simulator to track them, or scan a whole area to locate them. Mobile simulators have a working range of 1,600 feet, and while police may focus on a particular suspect, the device grabs every ISMI in the area. And that data can potentially be used in other cases, experts said.

While law enforcement agencies will use cell-site simulators for broad public surveillance, information about their deployment is hard to come by. Jacobs, the company that sold the state police its new simulator, does not mention them on its expansive website. But its proposal for the Mass sale is full of flowery language about the business with plenty of praise for its products along with descriptions of its capabilities and use in the field. There are also photos of the equipment.

“The unredacted version provides a lot of details,” said Cooper Quintin, senior public interest technologist at the tech watchdog Electronic Frontier Foundation. “This is the clearest picture that we’ve gotten of how cell-site simulators are operated, installed, and sold to police in years. … Having pictures of the devices is helpful for researchers, having pictures of the trucks is helpful for privacy rights advocates.”

The internationally wired Jacobs Technology, per its proposal, is the second-largest company in the US cellular infrastructure industry, and, as the industry’s “Honest Broker,” “drives innovation” with a “Culture of Caring” and the “promise that ‘We do things right.’” The company acquired longtime cell-site simulator manufacturer KeyW in 2019 and absorbed it into the company’s Engineering Integration Group. To date, Jacobs reports putting more than 300 such simulators in the field, via national intelligence agencies in the US, Europe, and Australia, as well as 40 state and local agencies like the Mass State Police.

That pedigree gives Jacobs the ability to not just meet but exceed bid requirements; per the proposal, the company provides “seamless geolocation and data gathering aimed at high powered vehicle based, mobile, mission critical operations.” The document also lists transmission information like radio bands and frequencies and emphasizes capability from 2G to 5G, along with giving equipment specs including:

- The [simulator] is a small form factor, cellular and Wi-Fi intelligence gathering tool for law enforcement. This low-power system is designed to be mounted in the user’s vehicle for covert, tactical deployment in any area of operation.

- The [simulator] is expandable and capable of supporting up to 27 radio cards for future expansion and could be deployed in up to three chassis for simultaneous use and operation in one software controller instance.

- The main operator can control the Base Station radios while another operator utilizes the built-in map interface, performs a database query for a cellular identifier, or performs realtime analysis of data during an intelligence operation in the field.

- [The interface] includes an integrated mapping solution with target range rings and a heatmapping display for immediate representation of where a target device is located. The heatmap is updated in real-time. The mapping solution also provides a visual breadcrumb trail to the operator in real-time.

The device alone costs nearly $250,000, with the basic accompanying equipment adding $350,000. An amplifier, purportedly intended to “minimiz[e] impact on non-targeted cellular use,” costs an additional $125,000. Plus the Silverado, which will cost $132,000 after installation and concealment of the simulator and its antennas.

“Tint will be installed to cover user requirements,” the proposal reads. “Additionally, tint will be installed into the truck cap to provide additional concealment. A windshield strip can be provided as well. … EIG’s integration will make every effort to achieve as much concealment as possible.”

As a bonus, after the simulator collects information, it can be easily sent to other agencies, according to the proposal.

“All mission data is available for export for future analysis if the user desires as well as sharing of data and analysis between other departments using this system for unified ease of interoperability,” per the Jacobs pitch.

Constitutionality concerns

Among the revelations in the bid response, Quintin of EFF said the specifications include new information about the capabilities of cell-site simulators.

“The fact that it integrates Wi-Fi collection, I think that’s the first time we’ve seen that confirmed,” he said. “They’re pretty hand-wavy about what Wi-Fi they’re collecting—the unique hardware addresses of every Wi-Fi card, or also what networks those addresses are trying to connect to. Your Wi-Fi card will constantly be reaching out to all the networks you have connected to—that is quite possibly what they’re trying to get. Your phone tried to connect to ‘Dave’s Home Network’ or ‘Work Wifi’—that might give a picture of who you are.”

The proposal also presents two “Example Cases” of how police departments have used these particular cell-site simulators—scenarios that civil liberties experts say show the dangers of surveillance overreach.

The first describes how Indiana State Police, “using a discreet, turn-key [cell-site simulator] platform provided by EIG, found and arrested four people in connection with a murder in the city of Kokomo, with two of the suspects charged with ‘murder and torture.’” The suspects were “nowhere on the Kokomo PD radar,” according to the example case, which provides links to local news coverage of the arrests.

But while those articles Jacobs refers to say police discovered a video that helped lead to arrests, it does not mention the use of the company’s cell-site simulators. It is unclear if their use was acknowledged in warrants or arrest affidavits, and Indiana State Police and the Howard County District Court did not respond to requests for comment. Departments using cell-site simulators often leave out any mention of their use when bringing charges, civil liberties advocates said, allowing authorities to avoid having to disclose that they were used without a warrant, or to prevent details about their deployment from entering court documents. Instead, cops can create fake convenient chains of evidence to account for their findings.

“Generally speaking, suspects should have the ability to challenge the constitutionality and legality of the means by which evidence against them has been gathered,” said Alex Marthews, founder of the privacy advocacy group Digital Fourth. “A practice of concealment like we have seen in cell-site simulator cases cuts against that basic rule of fairness in trial proceedings.”

Kade Crockford, director of the Technology for Liberty Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts, said requiring warrants for cell-site simulator use should be a no-brainer for law enforcement.

“If you’re only using this to find dangerous people or help investigate serious crimes, then getting a warrant shouldn’t be an obstacle and you should want to get a warrant so the defendant doesn’t have a reason to dismiss the criminal prosecution,” Crockford said. “There’s no good reason for anyone to oppose rules around these devices.”

The second example in the proposal is an overview of use in Fontana, California, a city of about 210,000 people east of Los Angeles. Police there have used Jacobs cell-site simulators for “many years,” and the materials note: “Over the last two years, their over 300 deployments of the system have been so successful, they ordered two new [cell-site simulators].” The tech has been tied to 169 arrests, the seizure of more than half a ton of methamphetamine, and the seizure of more than $9.5 million, according to the proposal, which also notes Fontana has assisted 40 “neighboring agencies” with such harvesting of information.

Quintin said he is concerned by how often Fontana was using and sharing its equipment: “Three-hundred times is absolutely overuse of this technology. If this is used at all, it should only be used in exigent circumstances where a violent fugitive is on the run or there’s a search and rescue mission.”

Foreseeing forfeitures, surveillance creep

The Mass State Police are purchasing the cell-site simulator from Jacobs using funds received through a $4 million 2023 COPS Anti-Heroin Task Force Program grant, through which the federal government gives states with high numbers of people being treated for drug abuse money for police investigations. That’s instead of treatment, but Sen. Eldridge said Massachusetts has been otherwise moving away from punitive drug-related law enforcement, and was concerned the new addition to the MSP arsenal could counter that.

“Given the source of where the money is coming from, there could be a focus on drug crimes,” Eldridge said. “As we’ve seen [with] Gov. Maura Healey’s decision to pardon misdemeanor marijuana convictions, there’s a real push to walk away from [punitive policies] and end the war on drugs.”

And Marthews of Digital Fourth noted that millions in seizures point to the potential abuse of civil forfeitures. By using a Stingray to obtain the phone info of people passing through an area associated with drug sales, police can potentially use those circumstances as justification for stopping drivers, searching cars, and forfeiting cash. Marthews said such drug-related funding means the staties could wind up with even more money to purchase, among other questionable tools, more surveillance.

“This can become a profit center for the state police,” he said, adding that a mobile device being in some way connected to what they consider another person’s phone used for illicit trafficking “would itself be enough to initiate a seizure.” Marthews continued, “Then, the asset owner would have to go to a hearing and prove the innocence of the asset in order to get it back. … The revenues from forfeitures can be used for more or less anything—more surveillance equipment, overtime, charitable benefits. Forfeitures are a black-box slush fund.”

Advocates also said the new apparatus could be used to collect information on any group of people—whether police have warrants or not—and raised concerns about how simulator are often used to target specific groups. “Law enforcement use of technology has tended to show bias and heavier use against minority populations than non-minority ones,” Katz-Lacabe of Oakland Privacy said.

Marthews said it is “a well-known dynamic in the context of police equipment and surveillance technology [that] once you’ve acquiesced to it, if there are not restrictions on its use built in up front, it will tend to be used toward everything down to routine drug busts. … They’ve got the tools, why not use them?”

Crockford said there will likely be significant political protests around this year’s national elections, and Stingrays could help facilitate mass surveillance and data sharing.

“Do people in Massachusetts feel confident and comfortable that technology like this wouldn’t be misused by the police to perhaps download a list of anyone who protested Donald Trump or anyone else, and hand that information to the FBI in a situation where the FBI is controlled by Donald Trump?” Crockford said. “That could put people at risk of serious harm. Those are the types of things that a policy with meaningful teeth, or even better—a law—would prevent in Massachusetts.”

Oversight and regulation?

While some cities, like Boston, require police to disclose what surveillance equipment they’re deploying and what they plan to get, there is no statewide law regulating the release of that information. Crockford said courts may deal with cell-site simulators on a case-by-case basis, but that doesn’t fully address issues like data retention and overreach—and it doesn’t come up if police are using the devices without a warrant to begin with.

“In some cases, the courts have been a little more specific and told police they’re required to delete information that’s not relevant to the investigation; but if you’re not getting a warrant, there’s no opportunity for the judge to do that,” Crockford said. “And if there’s no statute that requires police [to] minimize data collection and delete information that’s not relevant to their target, there’s no guarantee that every judge will require that. … The legislature ought to pass a law that imposes some checks and balances on police use of technology.”

Quintin agreed that Massachusetts lawmakers need to step in and establish guidelines and disclosures for Stingray use.

“[The legislature] needs to get on this immediately,” Quintin said. “There needs to be an independent non-police review of this technology. … There absolutely needs to be case law requiring a warrant for a simulator.”

California has statewide laws in place that specifically address cell-site simulators, requiring local governments to approve usage and a privacy policy for the devices before they are purchased. Katz-Lacabe said civil liberties advocates successfully sued the city of Vallejo in that state because officials tried to buy a Stingray without setting up a privacy policy. The company selling that Stingray to Vallejo? KeyW, the group that was eventually acquired by Jacobs.

And the City of Oakland has an even more intensive disclosure requirement, Katz-Lacabe said. Every year, the police department there has to produce a detailed report about its Stingray use. Requirements in the 2022 report, released in May 2023, include:

- A description of how the surveillance technology was used, including the type and quantity of data gathered or analyzed by the technology.

- Where applicable, a breakdown of where the surveillance technology was deployed geographically, by each police area, in the relevant year.

- A summary of community complaints or concerns about the surveillance technology, and an analysis of the technology’s adopted use policy and whether it adequately protects civil rights and civil liberties. The analysis shall also identify the race of each person subject to the technology’s use.

- Total annual costs for the surveillance technology, including personnel and other ongoing costs, and information on the source of funding for the tech in the upcoming year.

According to that report, Oakland PD did not use the simulator at all in 2022. Katz-Lacabe said requiring disclosure correlated with less Stingray use—and, conversely, a lack of disclosure tends to lead to increased surveillance.

“Oakland PD has to produce annual reports on their cell-site simulator—they have to report on the device’s usage, was it effective, did it locate the subject?” Katz-Lacabe said. “As a result, it’s never been used more than 10 times a year. … Other departments that do not have as much transparency do seem to use their devices a lot more.”

Sen. Eldridge previously chaired commissions investigating civil asset forfeiture and pushed for a bill requiring warrants for the use of facial recognition tech. In an interview for this article, he said he now plans to push for oversight of the MSP’s cell-site simulator.

“It’s extremely disturbing for the state police to be purchasing this piece of equipment when there have been a lot of documented abuses around surveillance, drug crimes, and general invasion of privacy,” Eldridge said. “I’ll be reaching out to state police leadership this week, trying to get more answers about why this is going forward.

“This is the second year of the Healey-Driscoll administration—it’s not just holdovers from the Baker-Polito administration. We’re looking through the lens of equity, privacy, racial justice, and the fact that people are becoming more and more concerned about who is using conversations and data and for what purpose.

“Clearly,” the senator added, “this needs a state action.”