“It was not a consensus, but still we feel it was the right thing to do based on the circumstances.”

It was even more exciting than that time back in 2008 when your friend in LA shipped you an unexpected ounce on the East Coast.

Free weed is one thing; freedom is another.

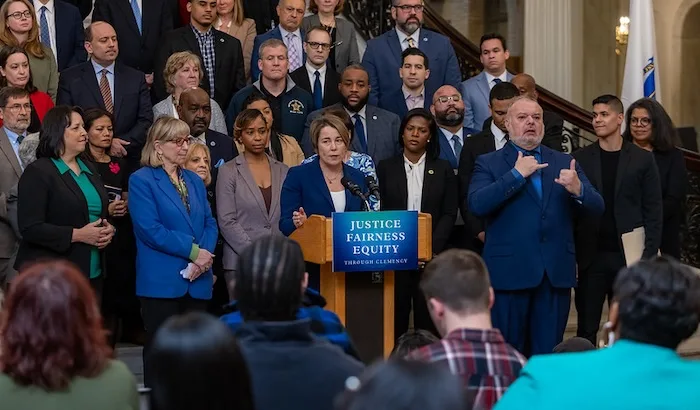

Last month, Gov. Maura Healey announced that she was exercising her “executive power … under the Massachusetts constitution, subject to approval by the Governor’s Council, to pardon all misdemeanor convictions for marijuana possession on record in our state.”

The announcement made national headlines; somewhere along the way, reporters started calling it the “mega pardon.” It’s an unprecedented move in how those “eligible [for the pardon] number in the hundreds of thousands,” as the governor put it in March. But while the pardon has been described by many as “sweeping,” it’s not a total sweep; as Devin Alexander, a graduate of the state’s first Social Equity Program cohort, noted at the press conference announcing the action, there will still be plenty of people with cannabis-related felony convictions living at a major disadvantage in the age of legal weed.

Before the misdemeanor pardons could become official, Healey needed final approval from the Governor’s Council, an obscure elected eight-member body that votes on all gubernatorial nominations for judgeships, public administrator spots, members of the Parole Board, and other critical positions and pardons (a commutation is a reduction in sentence; a pardon removes the underlying offense from the petitioner’s record).

Known in the past for general buffoonery and a tendency to rubber-stamp nominees whose approval was quietly courted and whipped way beforehand, the council has matured by some measures over the past couple of years and was on good behavior during this week’s meeting. (On the same day, in addition to the marijuana pardons vote, councilors voted unanimously to appoint a new member to the Mass Parole Board, Rafael Ortiz).

Early on, Councilor Terrence Kennedy asked about how these pardons will not remove information about the former conviction from someone’s physical record, but will rather still show that it happened, and was then pardoned. “I don’t think this is going to solve peoples’ problems, where we’re leaving this,” Kennedy said to Suffolk County District Attorney Kevin Hayden. The DA expressed openness to the extra step of expunging these kinds of charges, but said, “That’s a larger question for a different day.”

For now, Hayden came to speak for his office and to express the support of the Massachusetts District Attorneys Association: “Before, these charges were decriminalized by the legislature … This will deliver fairness and equity for those whose minor crimes came before legislative action and in so doing will allow people to move forward with their lives without the burden of a conviction for something that is now entirely lawful.”

Hayden also clarified some of the details around who and what the pardons apply to, and what they don’t excuse.

“It’s important to know that the governor’s proposal would allow only pardons for simple marijuana convictions—misdemeanor possession offenses,” the Suffolk DA said. “The pardon would not have an impact on more serious offenses such as marijuana trafficking and will not apply to all of the charges accompanying the simple possession comes with. For instance, if a person was convicted of an armed robbery and marijuana possession, the pardon would apply only to the possession charge.”

Later on, Councilor Tara Jacobs asked about people whose cases ended in a Continuance WithOut a Finding—frequently called a CWOF, in which the accused admits the prosecution has enough evidence to convict, but the court does not enter a guilty finding. Hayden recognized that there may be a gap omitting people with those kinds of records from this action, but said the state would have to look into what could be done about CWOFs, since this kind of pardon is unlikely to apply.

Newton Police Department Chief John Carmichael also popped in. The former hardcore prohibitionist turned surprising speaker of cannabis truths offered the blessing of the Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association, but noted the endorsement “didn’t come without controversy among law enforcement.” “It was not a consensus,” Carmichael said, “but still we feel it was the right thing to do based on the circumstances. And we don’t believe it minimizes the fact that other crimes may have been committed at the time when we’re just focusing on simple possession.”

While the Massachusetts blanket pardon is the first of its kind, according to a NORML analysis, “Governors of several other states—including Colorado, Nevada, Oregon, Illinois, and Washington—have similarly granted over 100,000 thousand pardons to those with low-level marijuana convictions.” Next up may be Minnesota, which is reported to have 60,000 expungements in store.

“Hundreds of thousands of Americans unduly carry the burden and stigma of a past conviction for behavior that most Americans, and a growing number of states, no longer consider to be a crime,” NORML Deputy Director Paul Armentano said about the national movement to pardon. “Our sense of justice and our principles of fairness demand that public officials and the courts move swiftly to right the past wrongs of cannabis prohibition and criminalization.”

“Massachusetts made history today,” Healey said in a media statement after the Mass vote. “I’m grateful to the Governor’s Council for their due diligence in approving my request to pardon all state misdemeanor marijuana possession convictions. … Thousands of Massachusetts residents will now see their records cleared of this charge, which will help lower the barriers they face when seeking housing, education or a job.”