Guest Opinion: Consumers and workers are being harmed by the failure of the CCC to use shelf testing and analysis of aggregated compliance test results to monitor the market.

The Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission’s management of cannabis testing has been criticized by many observers in the past few years. I am among them, but you don’t have to take my word for it:

- At the Cannabis Science Fair in December 2022, we revealed the prevalence of THC inflation, along with our discovery of harmful levels of bacteria and fungi in packages of cannabis flower sold in Massachusetts.

- An April 2023 Boston Globe editorial highlighted the lack of transparency and accountability for staff investigating testing labs for the CCC.

- In June 2023, Chris Hudalla of Proverde Labs and I spoke to podcast host Mike Crawford of the Young Jurks about numerous problems with the CCC’s management of testing, as documented by Talking Joints Memo.

- Chris Roberts wrote on MJBizDaily in July 2023 about potential conflicts of interest that entangle the director of testing at the CCC.

- This past April, Zack Huffman wrote on Talking Joints Memo about the ongoing problems with testing for microbial contaminants, which endanger the health of all consumers of cannabis.

- And just this month, the Mass inspector general publicly criticized the transparency and speed of the CCC’s investigation into the death of Lorna McMurrey after she fell ill at work for Trulieve.

Of the measures to better manage cannabis testing that have been suggested, a “standard lab” to be run by the CCC is the most expensive and would take the longest to implement. Estimates vary, but reasonable guesses are that up to $5 million and two years will be required to get a CCC lab started.

The reason for poor management of cannabis testing by the CCC, however, is a lack of care, not lack of assets. Consumers and workers are being harmed by the failure of the commission to use shelf testing and the analysis of aggregated compliance test results to monitor the market. The agency’s track record of alleged mistargeted enforcement, unclear guidelines, and unresponsiveness must be addressed directly and urgently.

What could explain the poor management of cannabis testing by the CCC?

Problems in the first several years can be traced to the handoff of oversight for testing cannabis from the Department of Public Health to the new commission at the establishment of the adult-use market in 2019. It’s likely the CCC scientific staff wasn’t ready for the change, and it’s also understandable that the team might have struggled at first.

Our data shows that THC inflation began to take off in Mass in mid-2021; by summer of 2022, it was discussed enough for us to begin our project researching it. By that fall, we were publicizing our results and had founded the Institute of Cannabis Science. I presented our research and a set of recommendations, including for shelf testing and analysis of aggregate data, at a meeting of the Subcommittee on Research of the Cannabis Advisory Board in December 2022.

At that time, commission staff became less responsive to our inquiries.

The director of testing for the CCC is James Kocis. We have a Certificate of Analysis from Steep Hill, a lab formerly operating in Mass, dated Sept. 15, 2022 for the client Trulieve that is signed by Kocis. That October, an article in MJBiz highlighted concerns about Kocis going to work for the CCC, since he had “worked as a manager for several years at Green Analytics [at the time, Steep Hill Massachusetts].” The article noted, “Speaking on background, several Massachusetts marijuana industry observers and players said Green Analytics was ‘known’ to be a lab where a cannabis company could find ‘friendly’ results.”

Kocis is not the only person from Steep Hill to end up at the CCC. Another analyst also worked there before going to work for the state, while a different analyst came from a testing lab, CDX Analytics in Salem, that shuttered earlier this year. According to reporting by cannabis blogger Grant Smith Ellis, that closure came after the firm informed its clients it would not follow new testing guidance issued by the CCC last November.

I have no direct experience that suggests wrongdoing by any of these CCC hires, but their potential conflicts of interest are troubling. From my own analysis of testing data, Steep Hill and CDX appear to be two of the lab companies that warrant the most investigation. So it’s hard to understand how their former employees can also be part of the solution.

There is a way to audit the cannabis market in Mass, grade the CCC’s management of testing, and stop the harm to cannabis consumers and workers without having a so-called “standard lab.”

While the notion of a single lab run by a government agency to establish the “ground truth” in disputes is understandable, it might make more sense in the future. Right now, more effective and economical interventions are available.

I manage the data for a collaborative study with five testing labs and five manufacturers of reference materials, the standards that calibrate the measurements of concentration for cannabinoid compounds. We could not assume that any reference material or lab was “correct,” so there was no “ground truth.” We were just measuring differences—across labs, and across manufacturers of reference materials. By comparing related series of data points, we produced conclusions about systematic differences between labs and manufacturers of reference materials, without arbitrary standards.

We recently outlined an approach in our publication, “Market Audits Combat Cannabis Misinformation,” in the American Society for Testing and Materials Journal of Testing and Evaluation. A key is “distributed analysis,” in which samples of cannabis are portioned for testing by multiple labs.

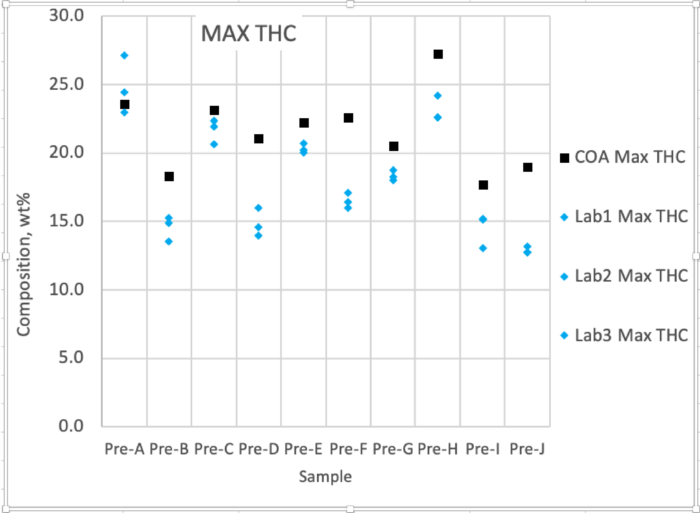

The figure accompanying this column displays some results from our shelf-testing of pre-rolled joints. We had three prerolls each of 10 strains from the same company, all tested by the same lab. We mixed together the contents of matching joints, divided the 10 samples in thirds, and tested two thirds at labs and one-third with the LightLab3 by Orange Photonics. I present here the total (max) THC from those three shelf tests as blue diamonds, with the values from the COAs (and labels) as black squares.

The blue diamonds don’t overlap each other perfectly because the three tests give results scattered by random error. The LightLab3 results cannot be distinguished from the two labs. If one of these three sources of analysis had been biased, we could have noticed that.

The distance between the blue diamonds and the black squares measures “THC inflation,” the difference between the label and the reality. By comparing the degree that the blue diamonds are scattered to their distances from the squares, we evaluate whether the difference amounts to random variation, or fraud.

“Distributed analysis” might appear to allow labs to game the system, but it doesn’t. The labs which participate are also the labs which provided the original compliance tests. They don’t know when they might be testing a product which they originally certified, and their results will be compared against those of their peers. A shelf test with distributed analysis is, effectively, also a “proficiency test” in which labs must demonstrate their competence to produce answers that are consistent.

Some calls for a “standard lab” in Mass are sincere, but some may be efforts to punt on more immediate reforms. Entrusting more resources to the CCC’s troubled testing department will not help the vulnerable consumers and workers of Mass cannabis. Deep reforms are urgently required.