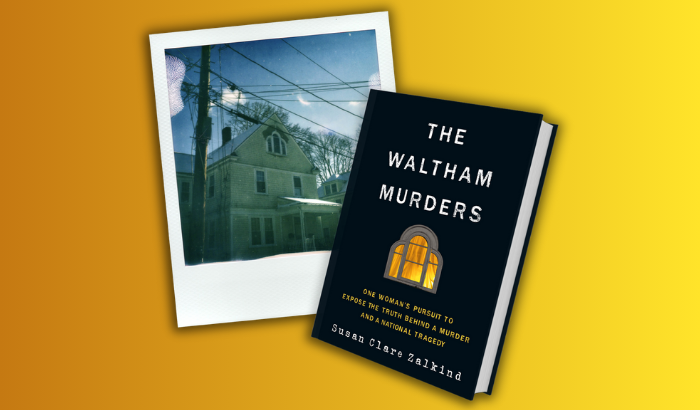

A chapter from The Waltham Murders: One Woman’s Pursuit to Expose the Truth Behind a Murder and a National Tragedy by Susan Clare Zalkind

Read our interview with Zalkind here

When I was nineteen, nothing could be more tedious than New England suburbia, the parks, pristine lawns, ice cream parlors, and baseball fields. Erik came into my life by way of a friend I’d known since nursery school. Back then, everyone called Daniel Adler-Golden DAG, and before he became a student of cannabis, carrying Jason King’s photobook The Cannabible around in his backpack, he’d studied classical music and magic tricks, walking down the halls of our high school burning sheets of flash paper.

The summer of 2006, DAG had a job as a caddy at the Chestnut Hill golf club. Erik was a golfer, and, along with a tip and his number, Erik gave DAG a bud of marijuana. The most beautiful nugget DAG had ever seen. After a few follow-up meetings, in which cash and plastic baggies were passed through car windows, the two became business associates. That evening in DAG’s bedroom, Erik passed around jars and extolled the virtues of crystals, the pungent aromas. It felt more like a wine tasting than a drug deal.

Erik was from across the river in Cambridge, Boston’s more liberal and academic sister city, but he fit right in with our suburban Newton crew. He was scrappy, with a quick sense of humor, and he was Jewish, like about half of my friends, which to me just meant he got our jokes. Erik talked the way we did, interrupting and speaking over each other when we got excited. L’chaim, we’d say as we passed the blunt around. Erik was loyal too, in that way that seems like a trope from a Boston crime movie but is actually true. People around here aren’t quick to make new friends, but when they do, the relationships tend to last.

The boys were in awe of Erik and his crystallized weed. I’d never seen them so impressed. I thought it was silly, and Erik was pretending to be a bigger drug dealer than he was, with his duffel bag of glass jars and his new sneakers. So I teased him for talking game. He told me he’d take me out and prove he wasn’t bluffing.

***

That summer, I was restless. Erik met me outside of a jazz club in Inman Square, a quiet neighborhood of Cambridge. I had a job collecting cash at the door, but mostly I sat in the stairwell, smoked cigarettes, and people-watched while the music vibrated through the old wooden floorboards. Later, with Erik’s encour- agement, I would get a weekly gig singing at the Irish bar next door.

Erik, then 26, pulled up in his blue Audi, rolled down the tinted window, and greeted me with a big grin and a head of mousy brown curls. I had my fingers wrapped around an unfiltered Lucky Strike and a wad of door fees in my dress pocket. He had a joint of his Sour Diesel rolled into a neat, clear paper cone and a bottle of Smartwater waiting for me in the car. He told me he was driving me someplace special.

We passed the joint between us as he drove, protected by his tinted windows.

It was good weed. Like, really good weed. Everyone I shared it with at the club would lose their goddamn minds. Expert growers tell me that even with the legal dispensaries open these days, it’s hard to find weed with such distinct properties. A lot of what is sold in stores today is mass-produced and comparatively bland. Cultivating and preserving high-quality cannabis plants was even more challenging during criminalization. The better the bud, the greater the risk for growers. Weed had to be grown in secret, and law enforcement could destroy entire crops at a moment’s notice, lock you up, and seize your home. Some of the best weed, like Sour Diesel, takes a longer time to grow. One grower I spoke to said Erik had a connection to Diesel—not Sour Diesel—through a group of men in Montecito, Santa Barbara. DAG says Sour Diesel is a controversial strain. In 2017 he founded Node Labs, where they preserve elite “old-school” and modern weed genetics. He credits Erik for launching his career. The original Sour Diesel was cultivated in the early nineties. It was the “loudest, stinkiest weed” you could find, and there was constant debate over “who had a fake cut.” DAG believes Erik most likely had a Sweet and Sour Diesel phenotype. In any case, back then, if you had a steady Sour Diesel connection, “you were the man.” Especially on the East Coast. It was just that much better than everything else around, and having it meant guaranteed business for the boutique dealers Erik sold to, like DAG.

Erik had unique variants in part because he sponsored artisan growers by giving them advance payments, and he worked with them to cultivate a variety of rare strains—in addition to supporting musicians and artists.

That night, when we were driving around in Erik’s car, felt momentous. The Sour Diesel warped my perception of time and added meaning to every movement and otherwise casual statement. I was drawn to Erik, and it scared me a little.

Erik drew on the joint and handed it back to me. I took another hit and slid down the leather seat of his Audi. We whizzed through the Williams Tunnel. The streetlights blurred until they looked like rings, and I imagined we were collecting them in some sort of virtual video game. He was driving me to Boston Harbor, where there was an Italian seafood restaurant beneath the federal courthouse. After Erik was murdered, I would return to the courthouse looking for answers.

The above excerpt was republished with permission from Little A. You can purchase The Waltham Murders here and follow the author at zalkind.info.