How Massachusetts State Police are using the opioid crisis to pursue “profound and dangerous erosions of privacy and civil liberties”

Imagine tailgaters partying in the parking lot of Gillette Stadium.

A large Silverado slowly rolls past the revelers. On the outside, it looks like every other pickup at the game, minus the Patriots bumper stickers. But behind the tinted windows and under the hardcover cargo shell covering the bed is a cluster of antennas and blinking lights.

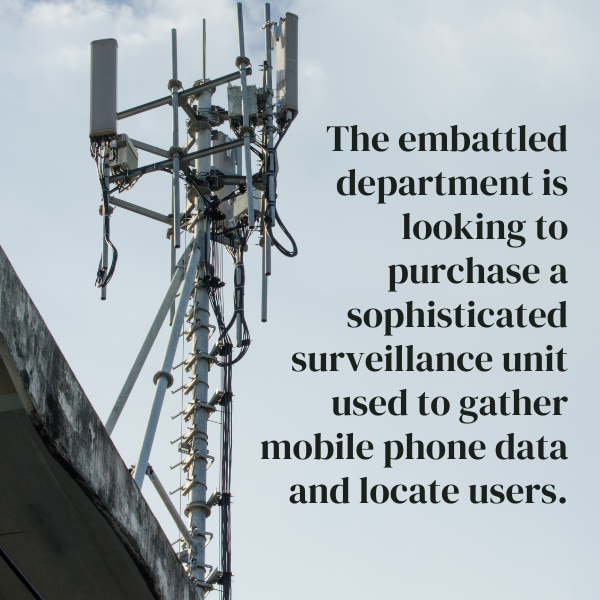

The truck belongs to the Massachusetts State Police, and it’s carrying a so-called cell-site simulator—a sophisticated surveillance unit used to gather mobile phone data and locate users. Police say they are trying to track one person, but in practice they are actually accessing every phone in the lot, and possibly into the stadium itself.

The above scenario could soon become reality throughout Massachusetts later this year, as state police look to purchase a new cell-site simulator (along with a Chevy heavy enough for the spy equipment) that can be used across the commonwealth, tracking tens of thousands—if not millions—of personal devices. The systems would be run by the same department that is currently rocked by a bribery scheme, in which troopers allegedly accepted snow blowers and bottled water as bribes in exchange for helping unsafe drivers secure commercial truck-driving licenses.

As the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism has shown in prior reporting, there is no substantial oversight of MSP procurement. In this latest example of the apparent opacity, civil liberties advocates said the department is downplaying the way simulators can invade cell phones and retain information. They fear the new tech could lead to suppression of free speech and questionable criminal cases, where prosecutors won’t reveal where they acquired information used to target suspects.

And while the police say they will use simulators to track fugitives or find kidnapped children, the million-dollar system is being paid for by a federal anti-heroin grant—which suggests the focus will be on drug cases, advocates said.

“The people in Massachusetts and the US really need to be aware of the degree to which the completely failed war on drugs is leading to profound and dangerous erosion of privacy and civil liberties,” said Kade Crockford, Director of the Technology for Liberty Program at the ACLU of Massachusetts. “They are impacted by the militarization of police and departments getting military-style technology to wage a failed war they’ll never win.”

The MSP request notes the simulator is being procured “to support activities associated with 2023 COPS AntiHeroin Grant award received by the MSP.” And the federal government’s description of how that grant money should be used is clear, saying it is “designed to advance public safety by providing funds directly to state law enforcement agencies in states with high per capita rates of primary treatment admissions for the purpose of locating or investigating illicit activities through statewide collaboration relating to the distribution of heroin, fentanyl, or carfentanil, or to the unlawful distribution of prescription opioids.”

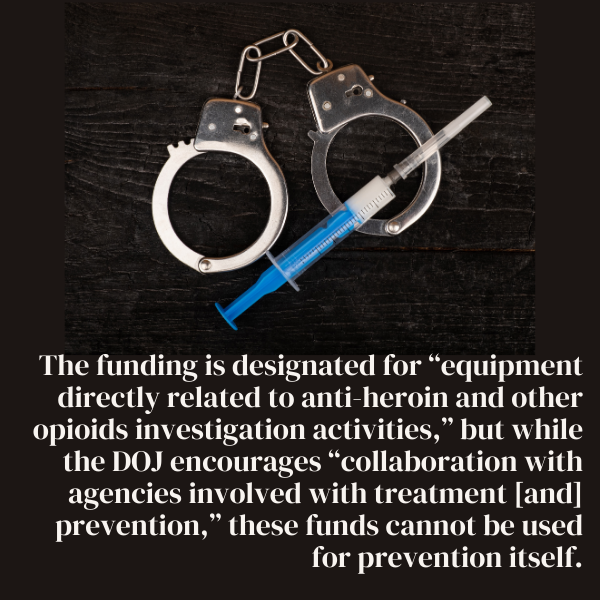

The grant funding does not focus on treatment for those admissions, though. A Department of Justice FAQ makes spending under the grant even more explicit, saying it can be used for “Equipment directly related to anti-heroin and other opioids investigation activities,” and “overtime for sworn officers and civilians engaging in anti-heroin and other opioids investigation activities.” And while the DOJ encourages “collaboration with agencies involved with treatment [and] prevention,” these funds cannot be used for prevention itself: “Agencies may only request funding for costs directly related to anti-heroin and other opioids investigative activities.”

Meanwhile, the Committee for Public Counsel Services has sued the state police for failing to turn over information about surveillance, and CPCS Forensic Services Director Ira Gant said use of a cell-site simulator could lead to citizens’ rights being violated.

“Capturing a person’s cell-phone signal and tracking them in real-time, as the state police aim to do with truck-mounted and handheld cell-site simulators, require a warrant supported by probable cause. To do otherwise violates the most basic of our constitutional rights,” Gant said. “The federal and state courts have routinely held that people have the right—absent proof they have committed a crime—to be free from police intrusion, including their devices.”

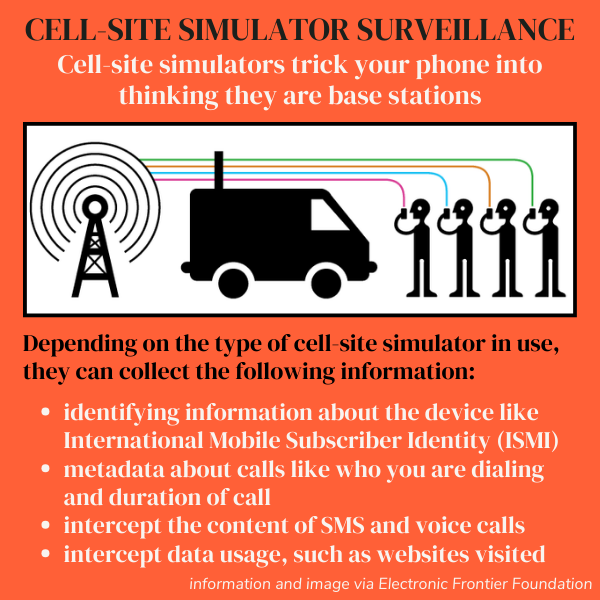

State police did not respond to questions about what kind of oversight the simulator program would have, how it plans to use the program, or how police would retain data collected through the simulator. Cell-site simulators work by broadcasting stronger signals than nearby cell phone towers, fooling cell phones into disengaging from those towers and connecting with the simulator instead.

While authorities often use “exigent circumstances” like kidnapping or an escaped fugitive to justify tracking a single person, a simulator grabs every phone in its radius, and as most simulators are mobile, that means it can pick up information from everywhere it travels. That information is used to triangulate cell phone locations—and could be used on the thousands of phones a simulator picks up, even if their owners are not the subjects of police investigation.

“You can use it at a gun shop to see who’s buying guns, at an abortion clinic to see who’s getting abortions, at a protest to see who’s protesting,” said Cooper Quintin, senior public interest technologist at the tech watchdog Electronic Frontier Foundation. “That’s where there are pretty significant concerns.”

“Police would be hugely interested in having all of the phone numbers of people attending a protest against police brutality,” said Alex Marthews, founder of the privacy advocacy group Digital Fourth. “They could hold onto those numbers and exploit the communications links they disclose without bringing prosecutions against those involved.

“Data is leverage.”

This article is syndicated by the MassWire news service of the Boston Institute for Nonprofit Journalism. You can read a longer version here. If you want to see more reporting like this, make a contribution at givetobinj.org