That time Ellsberg got stoned with Zinn while hiding from the FBI

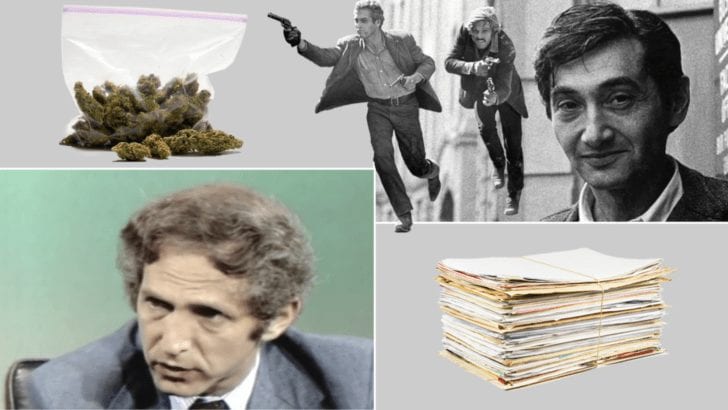

You’re probably familiar with the Pentagon Papers, whether from books, films, or because you lived through their release. Had the secret study of the Vietnam War not been leaked to journalists by legendary whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, who had worked on the papers as a military analyst, in 1971, it would have likely taken years or decades longer to know just how badly US government officials lied their dicks off to the public about so much foreign mayhem.

With the Pentagon Papers, and Watergate, and lots of sludge from the Godforsaken Nixon-Johnson era surfacing for obvious reasons, Ellsberg’s also been heard in the mix. Notably, he gave an interview to Reveal by the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIR) for its excellent podcast “The Pentagon Papers: Secrets, lies and leaks,” which expanded on the fascinating legend of the night before the story dropped.

As was already known from some of Ellsberg’s personal writings and the 2009 documentary about him by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith, The Most Dangerous Man in America, Ellsberg had religiously been going to see Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in Cambridge in the weeks leading to the release of the Pentagon Papers. Furthermore, he had been going with iconic Boston University professor and historian Howard Zinn. As Ellsberg recalled in a 2010 writing about Zinn, whom he called “the best human being I’ve ever known” and “the best example of what a human can be, and can do with their life”:

On Saturday night, June 12, 1971, we had a date with Howard and Roz to see Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in Harvard Square. But that morning I learned from someone at the New York Times that without having alerted me the Times was about to start publishing the top secret documents I had given them that evening. That meant I might get a visit from the FBI any moment; and for once, I had copies of the Papers in my apartment, because I planned to send them to Senator Mike Gravel for his filibuster against the draft.

Which is where Reveal comes in with the cannabis nugget:

Daniel Ellsberg: … I then picked up the phone and called Howard Zinn, who I was going to see that night to go see Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid for the fourth time or something, for me, I’d given Howard about a thousand pages of it, and Noam Chomsky about a [thousand 00:31:49], as historians, for their interest. They were keeping it under their bed.

Michael Corey [Reveal editor]: This next part makes you wonder, “What was he thinking?”

Daniel Ellsberg: I said, “Howard, I’ve got to store some more stuff with you. The FBI may come any minute.” I said, “Let me come by your place. I want to drop something off,” so somebody else also had given me a lid of grass.

Michael Corey: A lid of grass. That’s about an ounce of marijuana.

Daniel Ellsberg: I thought, “Okay, they’re going to come any minute, here,” so he took the lid of grass there, and I gave Howard the stuff, and then we smoked as much as we could, and threw, and flushed the rest down the toilet.

Michael Corey: Yeah, so while Ellsberg was dodging the FBI in a movie theater, baked and watching Butch Cassidy, the presses were rolling for the Sunday paper.

Al Letson: It’s June 13, 1971, and just past midnight, the first edition hits the street. The team at The New York Times is huddled, wondering what comes next. At the White House, President Nixon will wake up to get a briefing he didn’t expect.

Finally, here’s Ellsberg’s account from his 2002 book, Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers, which brings home all the Boston-centric details of this major day in history, cloudy as the memories may be …

I had to get the documents out of our apartment. I called the Zinns, who had been planning to come by our apartment later to join us for the movie, and asked if we could come by their place in Newton instead. I took the papers in a box in the trunk of our car. They weren’t the ideal people to avoid attracting the attention of the FBI. Howard had been in charge of managing antiwar activist Daniel Berrigan’s movements underground while he was eluding the FBI for months (so from that practical point of view he was an ideal person to hide something from them), and it could be assumed that his phone was tapped, even if he wasn’t under regular surveillance. However, I didn’t know whom else to turn to that Saturday afternoon.

Anyway, I had given Howard a large section of the study already, to read as a historian; he’d kept it in his office at Boston University. As I expected, they said yes immediately. Howard helped me bring up the box from the car.

We drove back to Harvard Square for the movie. The Zinns had never seen Butch Cassidy before. It held up for all of us. Afterward we bought ice-cream cones at Brigham’s and went back to our apartment. Finally Howard and Roz went home before it was time for the early edition of the Sunday New York Times to arrive at the subway kiosk below the square. Around midnight Patricia and I went over to the square and bought a couple of copies. We came up the stairs into Harvard Square reading the front page, with the three-column story about the secret archive, feeling very good.