“Mass has led the way across the nation in terms of our regulations … and laws around equity. But do we actually actualize them? Many people here will say no.”

Panacea is a word that means cure-all, or broad solution. It’s also the name of a dispensary in Middleborough, Mass where Harry Jean-Jacques recently introduced a group of entrepreneurs to a room of attendees. Most people there were part of the legal cannabis industry, with many seeking to start businesses of their own if they hadn’t already.

The Big Hope Project, founded by two brothers from Dorchester, is a nonprofit organization that aims to not only help Black business owners secure funding, but also prepare them for the barriers and pitfalls ahead. Their most recent events have included a seminar at Panacea in January, and the Big Hope Awards, an event held in Roxbury last week that recognized activists for their work in the legal cannabis industry. Leaders of the project are challenging ideas about legal cannabis, and say more should be done to counteract years of damage done to communities by the war on drugs.

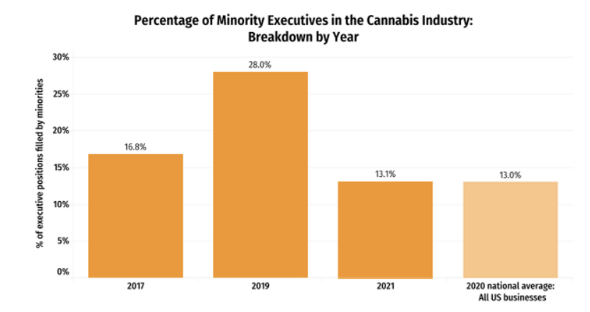

A study by MJBizDaily shows minority professionals made up 13% percent of cannabis industry executives in 2021, while another study showed 19% in an ownership position that year. That data does not skew significantly from the average for other industries, and remains a source of frustration for workers, organizers, and entrepreneurs who hope for the legal cannabis industry to be a force of change.

In 2022, the cannabis industry brought in more than $4 billion in revenue for Massachusetts and powered more than 27,000 jobs. The overall economic benefits are undeniable, but activists say those benefits are not being shared with the people who need it most. For small business owners looking to build a dispensary, the initial costs are an immense hurdle, ranging from $300,000 to in excess of $1 million, depending on the location.

In addition to the time and resources needed to gain a license from the Cannabis Control Commission, cannabis is also still federally illegal, making people with history in the illicit cannabis trade more hesitant to participate. While the debate over broad legalization continues, one recent court ruling made the risk for potential business owners even higher, stating that Massachusetts cannabis workers are unable to file for bankruptcy and receive the same benefits as someone filing from another industry.

Massachusetts legislators recognized that these potential issues were becoming real and present barriers to entry, and set up a fund for those impacted by the war on drugs. The cannabis equity bill, signed by Charlie Baker last year, also removed certain rules that can disqualify potential dispensary owners, and granted dispensaries the same state tax benefits as other legal businesses. The equity fund is expected to provide more than $20 million per year in financial support, but according to organizers at the Big Hope Project, it’s not enough. Co-founders Harry and David Jean-Jacques say the answer is simple: put more minority cannabis workers in positions of leadership, and in addition to funding, make sure they have the tools to succeed.

“We’ve literally shown how to create equity via workforce development, free expungement, free education, all these things that the state isn’t doing, the principalities aren’t doing, definitely the cannabis companies aren’t doing,” Harry said. “We’re already doing the work, we just want to scale up and help the most people we can.”

One discussion at Panacea centered around the concept of co-branding, a marketing technique that involves using one brand to raise awareness for another. Jean-Jacques said while the practice can lead to exploitation for minority business owners, it can also be a powerful asset if done correctly. Learning through doing, the nonprofit recently launched a “Black labeling” program that certifies a cannabis product is coming from a Black-owned business.

Yvette, a small business owner who plans to relocate from New Jersey to Mass, said her goal is to open doors for anyone who associates with her. She also strives to make good on the ideal that anyone can come to America and pursue goals of their own.

“It’s a blessing to get together, to get more knowledge,” she said. “As long as you put the hard work in, and you have a good team, you can make it happen.”

Satin Faulkner is an entrepreneur who creates organic skin care products as well as THC-infused topicals, and is now looking to enter the legal industry. Faulkner is a longtime friend of the Jean-Jacques family and said it’s been inspiring to work on the project: “I feel like it’s great to foster relationships with people who are like-minded, who are motivating and uplifting the community. It’s very inspirational.”

At last Friday’s event, Harry asked for a show of hands from anyone who was impacted by the drug war, or saw someone close to them impacted; despite varying definitions, nearly everyone’s hand went up. Sebastian was no exception, and joined a panel of speakers sharing their unique experiences. “I had a lot of issues with having an arrest on my record, and saw they were doing expungement work,” he said.

Part of Sebastian’s agreement with the CCC as a social equity beneficiary is that he planned to host a seminar on restorative justice. He discovered that the Big Hope Project had already started such a program, and seeing a chance to collaborate, Sebastian reached out to Harry. They’re now collaborating through events like the one held at Panacea.

As “legacy” professionals, panelists worked in the cannabis trade before legalization, and while their transition to a formally established market has brought many new challenges, they brought a wealth of experience and knowledge that can help newcomers make the best use of the resources available to them. In his case, Rafael Guzman said that while entering the legal cannabis industry has been a challenge, he still prefers it to the constant stress and danger of the illicit drug trade.

“Having an open mind, knowing that people are gonna look at you differently—it doesn’t matter as long as you have your world set in place, and you’re doing the right thing, and trying to get the people around you to do the right thing.”

A legacy cannabis worker, Guzman said it took a lot of growing and maturing to reach where he is today. He currently runs the Summit Lounge, a club in Worcester that hosts a variety of members-only events. Harry said despite the project’s initial success, there are still many hurdles ahead.

“We probably get 50% of the funding compared to our white peers,” Guzman said.

While recognizing the long road ahead, the growing community took a moment to celebrate its progress at the Big Hope Awards. The event took place at Black Market in Roxbury Friday night, where presenters chose a group of professionals who best represented that progress: “Hope stands for Honor, Outreach, Philanthropy, and Equity … and we’re giving the award to people who encompass that.”

Richard Harding took the stage to accept the Third Eye award for business development. Harding fought to establish a legal cannabis operation in 2019, at a time when only two of the 184 business licenses were held by owners with social equity status. He helped form a coalition called Real Action for Cannabis Equity, and said in an industry seen as progressive, open discrimination is still an obstacle. Harding described a tense encounter that happened outside a cannabis networking event: “So there’s this white guy, he had a shirt on. It said, “Buy Weed From Rich White Men.’” Harding explained how his team took that negative experience and turned it into positive action, pushing forward to raise $15 million for the venture that would become Green Soul Organics.

Meanwhile, Harding said another barrier to equity is when business owners are convinced to give up their long-term value. “We’d sit down and have great steaks with a bunch of white millionaires, who would basically say, Let us give you a mil, a bag, and we’ll take over and you’ll be the front for the company. We decided early on, from all the things that we came up through, that we were gonna bet on ourselves.”

Friday’s keynote speaker was Shekia Scott, who accepted the Beacon of Hope Award. Scott is an activist and organizer who worked to establish the first statewide cannabis equity program in the nation.

“Why are we still at the beginning?” Scott asked. “Why every time we get to this point, is it, We still have a long way to go? How much longer do we have to go?”

Scott now serves as the cannabis business manager in the City of Boston Mayor’s Office of Economic Opportunity and Inclusion, where she works to provide assistance to cannabis entrepreneurs at every stage of development.

“Massachusetts has definitely led the way across the nation in terms of our regulations, our state mandates, and laws around equity. But do we actually actualize them? Many people here will say no.”

While Scott has worked to establish more resources for minority business owners, she said it takes sustained action and organizing to create lasting change.

“You cannot actualize equity through a program,” she said. “None of this was manufactured through programs, so it can’t be undone through programs.”

David Jean-Jacques, who handles outreach and media planning for the project, said he continues to search for new avenues of growth, along with other socially responsible companies who want to give back.

“Try to make a positive impact on the community, and create change,” he said. “One day at a time … or, one spliff at a time.”